The Puritan's Basement

I. THE BEETLE

The car was a 1968 Volkswagen Beetle, tan, the color of nothing. The color of parking lots and motel stucco and the sky before rain that never comes. He had removed the passenger seat and stored it somewhere no one ever found. In its place was a space. In the space he put them.

The cast on his arm was plaster and gauze and he made it himself in his apartment and practiced the wince. The crutches he bought at a medical supply store on Aurora Avenue and kept in the back seat with a crowbar wrapped in a towel. He approached them in parking lots. At bus stops. On the edges of campuses where the light was going and the buildings threw long shadows and a girl might be walking alone to her car with her books held against her chest. Could you help me. I can't carry this. My car is just over there.

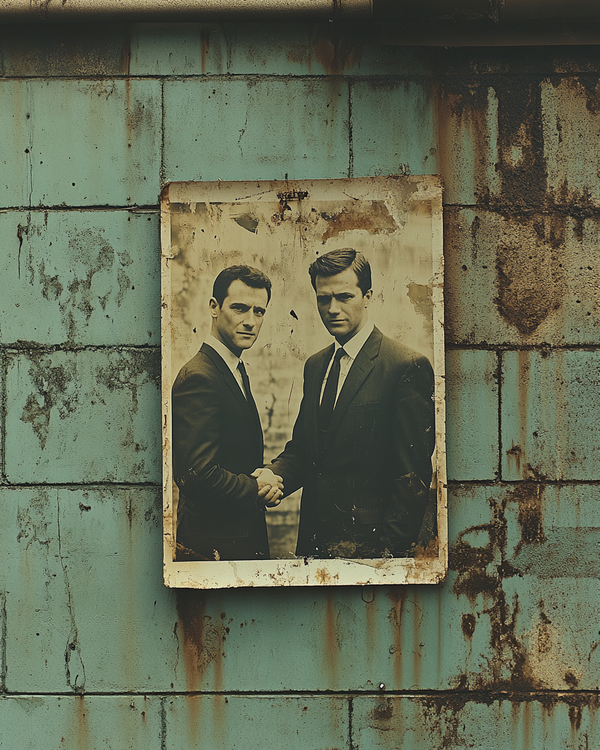

He was handsome. Everyone said so. He had a jaw and good hair and he knew how to hold a gaze for a half second longer than expected. He looked like the kind of man their mothers had told them to hope for. Thirty women got into his car.

His psychology professor at the University of Washington wrote him a letter for law school. "I would place him in the top 1% of undergraduate students with whom I have interacted," Ronald E. Smith wrote. "Exceedingly bright, personable, highly motivated." The professor had sat with him for years. Had graded his papers on human behavior. Had looked at his face across a desk and seen a bright young man, a future professional, someone who understood how people worked. The women in the parking lots saw the same thing. The seeing was the trap.

He lost count. He said so later. Washington, Utah, Colorado, Florida. He moved across the country like a narrative looking for new chapters and the chapters were bodies and the bodies were young women who looked alike, who looked like Stephanie Brooks, who had broken their engagement in 1968, who had told him he was going nowhere, who had refused to become the mirror in which he could see himself as real. He spent the rest of his life proving her right in the only way he understood. He went somewhere. He became someone. The somewhere was a crawl space. The someone was a god of a very small and very dark room.

II. THE NUMBER

Here is a number: seventy-four percent of the world's known serial killers are American. Four percent of the global population producing three quarters of the men who kill strangers for the pleasure of killing. The number has been studied. The number has been cited. The number sits there waiting for someone to explain it.

Maybe the number lies. Maybe America is just better at catching them, cataloging them, giving them names and Netflix specials. Maybe other countries bury their dead in statistics that never get counted. Maybe the FBI's databases and the cable news infrastructure and the true crime industry have built a machine for seeing what other nations leave in the dark. This is possible. This is worth considering. But even if the number is half wrong, even if it's fifty percent instead of seventy-four, the question remains. Why here. Why us. Why so many.

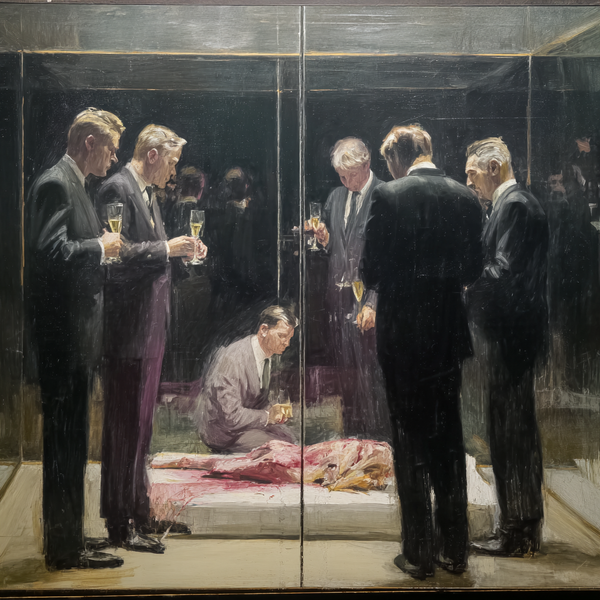

Here is another number: zero. That is how many times you have heard this question discussed on cable news, in presidential debates, in the opinion pages that tell you what to worry about and what to ignore. School shootings, yes. Mass shootings, yes. But the men who kill women one at a time, in bedrooms and basements and along the sixty thousand miles of interstate highway, the men who are not aberrations but a pattern, who are not exceptions but a product line: them we do not discuss. We make them into movies. We do not ask why there are so many of them. We do not ask what factory keeps producing them. We watch.

III. THE FACTORY

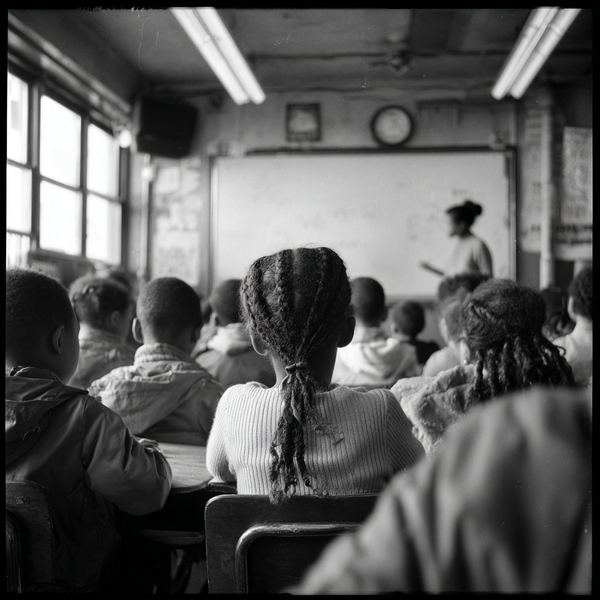

The factory opened in 1630. The Puritans did not know they were building it. They thought they were building a city on a hill, a beacon to the nations, a new Jerusalem in the Massachusetts wilderness. They carried with them a book and a terror. The book said the body was fallen. The terror was that they believed it. The flesh was corruption. Desire was the devil's whisper. The woman's body especially: Eve's body, the body that had reached for the fruit, the body through which sin had entered the world and through which it would enter again if given half a chance, a loose button, an unchaperoned moment, a thought that lingered where thoughts should not linger.

They buried the body. Not literally. Worse. They buried it in the mind. They taught their children to bury it and their children taught their children and the burial became so deep, so automatic, that it no longer felt like burial. It felt like virtue. It felt like civilization. It felt like the natural order of things: the spirit above, the flesh below, the basement sealed, the door locked, the key thrown into the sea of forgetting.

But here is what the Puritans did not understand, what perhaps they could not have understood, what four hundred years of American history has been the slow and bloody process of learning: you cannot kill desire by burying it. You can only teach it to dig.

IV. THE BINARY

He had a girlfriend. Elizabeth Kloepfer. He dated her for seven years. He slept in her bed and met her daughter and talked about marriage and went to church with her on Sundays. She cooked him dinner. She did his laundry. She called the police when she saw the composite sketch and thought it looked like him, and then she told herself it couldn't be, and then she let him back into her bed.

The women he killed looked nothing like her. They were younger. They parted their hair in the middle. They looked like Stephanie Brooks, who had left him in 1968, who had told him he wasn't good enough. He killed women who looked like the woman who had refused him and he went home to the woman who hadn't. This is the arithmetic. This is the grammar. The virgin you keep. The whore you bury in the woods.

The Puritans would have recognized it. They built the categories. They drew the line and told their sons which women went on which side and what you were allowed to feel about each. Four hundred years later a man in a tan Volkswagen was still sorting.

V. THE COURTROOM

The courtroom in Miami was air- conditioned and fluorescent and packed with young women who had come to see him. They were attractive, single, the same type he had killed. They watched him like he was a matinee idol. One of them described him to a reporter as "fascinating." Another said he had "magnetism." He winked at them from the defense table. He smiled. He was representing himself, and the performance was the best of his life.

He had bitten one of the women so hard that the mark on her body matched his teeth. He had beaten her with a log while she slept. He had done this to two women in one night, in a sorority house, moving from room to room. He did not rush. One of them lived long enough to hear him in the next room. The jury heard the testimony. They saw the photographs. They deliberated for less than seven hours. Guilty. Death.

But that was 1979. He lived another ten years. He gave interviews. He got married in the courtroom, exploiting a loophole in Florida law. He fathered a child on death row. He consulted with the FBI on other cases, an expert now, a colleague. He appeared on television. He smiled for the cameras. The families of the dead women watched him become famous. They watched him explain himself. They watched the country that was supposed to kill him make him into a star instead.

The women he killed have no Wikipedia pages. Most of them. You can find his page in three seconds. Thirty thousand words. His childhood. His psychology. His methodology. His quotes. The women are listed in a table halfway down, name and age and date, like a box score, like statistics, like they were the supporting cast in the story of his life.

Then Judge Edward Cowart, who had called the crimes "extremely wicked, shockingly evil, vile," turned to the man he had just condemned and said this: "Take care of yourself, young man. I say that to you sincerely. You're a bright young man. You'd have made a good lawyer and I would have loved to have you practice in front of me, but you went another way, partner. I don't feel any animosity toward you. I want you to know that."

Partner. The word hangs there. The judge who had just sentenced a man for raping and beating women to death called him partner. Wished him well. Said he bore no ill will. The women in the gallery swooned. The women in the photographs were dead. The women watching at home thought: how sad that such a bright young man went astray.

No one asked how the country that made him could also be the country that loved him.

VI. THE CONFESSION

The night before they killed him he gave an interview to James Dobson, the evangelical leader. He blamed pornography. He said dirty magazines had done this to him, had awakened something that should have stayed asleep. Dobson nodded. Dobson released the tape. The tape became proof that the Puritans were right, that the body must be buried deeper, that the flesh is always climbing out of the grave.

But notice what he was doing. Even at the end. Even with the chair waiting. He was working the room. He was giving the culture what it wanted to hear: an external cause, a serpent, a fruit he should not have tasted. He was speaking the Puritan grammar perfectly. The flesh made me do it. The woman's body, even in pictures, even in representation, reached out and corrupted me. I am not the product. I am the victim.

The crowd outside the prison cheered when they threw the switch. They set off fireworks. They chanted "Burn, Bundy, burn." They had come to enjoy a killing that was sanctioned, a violence that was justice, a murder that was not murder because the state had signed the paperwork. Two thousand volts through the body that had destroyed so many bodies. They sold T-shirts. They tailgated. They had the time of their lives.

And then they went home and watched the documentary.

VII. THE WATCHING

Seventy-three percent of true crime consumers are women. They listen to podcasts about women being murdered. They watch documentaries that show his face for ninety minutes and her face for twelve seconds. They learn the names of the killers. They do not learn the names of the dead.

Why. This is worth asking. Why would women choose to spend their evenings with stories about women like them being raped and strangled and left in the woods. The official answer is education. They are learning to survive. They are studying the predator's methods so they can recognize him in the parking lot, at the bus stop, on the edge of campus where the light is going. They are doing homework for a test they never asked to take.

But there is another answer, and it is worse. They are rehearsing. They are watching their own deaths over and over because the culture has taught them that this is what happens to women, that this is always a possibility, that the parking lot is never safe and the man with the cast might be real. They watch because the watching is a way of controlling what cannot be controlled. If I study him enough. If I learn his face. If I memorize the signs. Maybe I will be the one who gets away.

And there is a third answer, the one no one wants to say. They watch because the culture has made these stories exciting. Because the documentaries are well-lit and well-scored and the killer is handsome and the narrative has a shape. Because we have taken the worst thing that can happen to a woman and turned it into content. Because the machine that produces the killers also produces the audience, and the audience is not separate from the machine.

Bundy. Say the name. Everyone knows it. Everyone knows his face, his jaw, his hair, the way he smiled in the courtroom. Now say the names of the women. Lynda Ann Healy. Donna Gail Manson. Susan Rancourt. Roberta Parks. You have never heard these names. You will forget them by the end of this sentence. Their faces are in the B-roll. Their lives are the raw material from which the story of the man is made.

This is not an accident. This is the structure. The woman is the flesh and the flesh is where the story happens. She is the medium. He is the message. We watch because the culture that produces these men also produces the appetite for them. We call the appetite fear. We call it entertainment. We call it a warning. We never call it what it is.

VIII. THE QUESTION

Here is the question no one asks: why here? Why this country? Why not Ireland, which had the Church and the Magdalene laundries and its own terror of the flesh? Why not Spain, which had the Inquisition? Why not any of the countries that taught their children the body was sin?

I do not have a complete answer. Anyone who claims to is selling something. But here is what America had that the others did not: the Puritans and the frontier. The repression and the escape. The theology of the buried body and sixty thousand miles of interstate highway on which to hunt. The most car-dependent nation on earth, where a man could kill a woman in Washington and drive to Utah and kill another and no one would connect them for years. The most mobile society in history, where strangers meet strangers in parking lots and the old village structures that might have noticed a monster are gone, replaced by nothing, replaced by the freedom to disappear.

And the myth. Do not forget the myth. The American killer is the dark cousin of the American hero. The self-made man. The frontiersman. The lone individual who needs no one and makes his own rules and conquers the wilderness by force. Bundy talked about himself like he was a pioneer. Like he had discovered something. Like the women were territory.

The Puritans buried the body. The frontier taught their sons that violence was how you claimed what was yours. The car gave them the weapon and the escape. The myth told them they were heroes. Put it together and you get a factory. You get seventy-four percent. You get Ted Bundy smiling for the cameras like he had earned something.

IX. THE SILENCE

A detective who worked missing persons for twenty years said something once that has stayed with me. He said the hardest part was not the bodies. The hardest part was the families who stopped calling. The mothers and fathers who phoned every week at first, then every month, then every year, then not at all. They gave up. They learned what the culture had been teaching them all along: some women disappear. Some women are not searched for. Some bodies are found and some bodies are not found and the difference has nothing to do with the bodies and everything to do with what kind of woman the body used to be.

Bundy's victims were college students. Sorority girls. Women the newspapers called coeds, which is a word that means a woman who is still clean, a woman who is still marriageable, a woman whose death is a tragedy rather than an inevitability. These were the women America searched for. These were the women whose faces made the evening news. The grammar sorted them into the category that mattered, and so their killer became famous, and so their killer became a story we tell ourselves over and over, and so we learned his name and forgot theirs.

X. THE ENDING

I do not know how to end this. The ending would require a solution and there is no solution. The ending would require a turning, a redemption, a moment when the culture looks at itself and sees what it has made and decides to make something else. The ending would require Americans to admit that the basement is not a metaphor, that the bodies are not symbols, that the seventy-four percent is not a mystery but a confession.

We will not admit this. We will watch the next documentary. We will learn the next name. We will shake our heads at the monster and never ask who taught him to be monstrous. We will bury the body again and again and wonder why it keeps climbing out of the grave.

XI. THE PARKING LOT

Somewhere tonight a woman is walking to her car. The lot is almost empty. A man approaches her. He is handsome. He is clean. He has a cast on his arm and a story about needing help and a face that looks like the face of someone who can be trusted.

She was raised to be kind. She was raised to help.

She stops.

You know his name. You do not know hers. You never will.

She gets in.

This is not a metaphor. This is Tuesday. This is the country working as designed.

© 2026 August Holloway / Dead Letter Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form without prior written permission.