They Have Always Been Coming

Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent. Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

I. The Frontier

They have always been coming. In the national dream they mass at the edge of the known world and their fires light the darkness and in the morning the darkness is closer. This is the oldest story. It was old before there was a name for the land they would take and name themselves after.

Mary Rowlandson wrote it down in 1682. Taken from her house in Lancaster in the hours before dawn. Husband elsewhere. Children scattered or killed. Carried into the wilderness by the Narragansett and held eleven weeks and ransomed back and never the same. She published the account and it sold and sold. They called these stories captivity narratives and they became a genre and then a grammar and the grammar never broke.

But the grammar shifted. Rowlandson's captivity was theological. God testing the saint. The wilderness as spiritual trial. The Narragansett were instruments of divine pedagogy, not yet quite human, not yet quite animal, suspended in the Puritan imagination as figures of holy danger. She could eat with them. She could learn their words. The return was to grace.

A century later the narrative hardened. The captivity of Frances Slocum, taken by the Lenape in 1778, became a story about blood. She lived sixty years among them. Married. Had children. Refused to return. When her white family found her she said she was Lenape now and the finding was not a rescue but a violation. The newspapers called it tragedy. They meant contamination. The theological had become biological. The wilderness was no longer trial but infection.

By the time Cynthia Ann Parker was taken by Comanche in 1836, the narrative had become frankly racial. She too married. She too had children. One of them became Quanah Parker, the last chief of the Quahadi band. When Texas Rangers recaptured her in 1860, she wept. She tried to escape back to the Comanche. She died grieving for her sons. The captivity narrative now had a new terror at its center: the white woman who preferred the savage. The body that would not come home.

This is the transformation the easy version skips. From Rowlandson to Parker, the captivity narrative loses its theology and gains its race science. The savage becomes a category of blood rather than a condition of soul. The wilderness becomes a place that changes you permanently, biologically, a contamination zone from which there is no real return.

•

In Vietnam they rebuilt it again. The POW narrative was not about blood contamination. It was about will. The Hanoi Hilton as forge of American manhood. John McCain's broken body becoming proof of national virtue. The captivity here was explicitly imperial: Americans held by those who should have been grateful for American presence. The return was triumphant. The trauma was transformed into credential.

But notice what the Vietnam narrative required. It required that the war be just enough to make the suffering meaningful. The POWs could not be victims of American policy. They had to be victims of Vietnamese cruelty. The captivity narrative does this work. It makes the imperial project invisible by focusing on the imperial body in chains.

Now they are the caravan. They mass in the app on your phone, numbers ticking upward, red arrows pointing north. They are filmed from drones and from helicopters and from the phones of people who film them to prove they exist. The filming is the new captivity. You are held by the image. You cannot look away. You are taken from your house without leaving it.

And here the narrative shifts again. The contemporary captivity is not theological (Rowlandson), not biological (Parker), not volitional (McCain). It is demographic. The terror is not that they will take our women. The terror is that they will become the majority. The great replacement. The browning of America. This is a captivity narrative for an age of statistics: we are being taken not by violence but by birth rate.

The nation that built itself on taking now fears being out-numbered by the taken. The colonies are walking north. The children of the Monroe Doctrine are coming to collect.

•

Listen to how they talk about the border and you can hear the grammar underneath. The attack comes without warning. The settlement is breached. The women and children. Always the women and children. But now the fear is not that they will carry off our daughters. The fear is that our daughters will marry theirs. The biological contamination has become cultural. The wilderness is no longer out there. The wilderness is the quinceañera next door. The Spanish on the signs. The new neighbors who will not wave back.

Manifest destiny required Indians at the gates. Overseas expansion required savage Filipinos. The Cold War required dominoes falling toward California. The terror war required them to hate our freedom. Each expansion produced the captivity narrative that justified it. The sequence is always the same: we move into their space, they become a threat, we were here first.

Now there are American military personnel in Okinawa, where the locals protest their presence. In Djibouti, at Camp Lemonnier, watching the Horn of Africa. In Bahrain, headquarters of the Fifth Fleet, on an island that crushed its own Arab Spring with Saudi tanks and American silence. In Diego Garcia, which required the forced removal of every Chagossian to make room for the runways. In Guantánamo, on land that Cuba has refused to lease since 1959, a base held by nothing but the unwillingness to leave. Eighty countries. Somewhere between 750 and 800 bases. The numbers are disputed because some of the installations are secret and some of the definitions are flexible and some of the presences are denied.

This is not defense. Defense is local. This is the projection of power so total that it becomes invisible to the ones projecting it. They think they are normal. They think the way they live is the way people live.

And yet. The wall. The camps. The children separated from parents and held in facilities that the government's own lawyers argued did not require soap or toothbrushes. The Processing. The Removal. The paperwork that makes the imprisonment into administration. The most powerful nation in history is afraid of unarmed people walking north.

The captivity narrative explains this because the captivity narrative is not about reality. It is about need. The need to be the one who was wronged. The need to have been taken so that the taking you do is already justified.

II. The System

The waiting room at the USCIS field office in lower Manhattan smells like the inside of a photocopy machine. Toner and static and the particular human musk of people who have been sitting too long in chairs designed to discourage sitting. The chairs are blue. The blue is the blue of nothing, the blue of procurement catalogs, a blue chosen by someone who would never sit in it.

There is a screen on the wall. It shows numbers. The numbers are being served. G-267. H-114. The letters indicate categories and the categories indicate futures. G is good. H is less good. There are other letters that are worse. The people in the room watch the numbers change. They hold paper numbers of their own. The paper is white with black ink and perforated edges and looks exactly like the paper you take at a deli counter. The futures are distributed like cold cuts.

A woman in the third row has a folder. The folder is white. Inside the folder are other folders, different colors, each color a document category. She has organized her life into document categories. Birth certificate, apostilled. Marriage certificate, apostilled and translated by a certified translator whose certification is also in the folder. Passport. I-94. I-797. I-485. The forms have names that are also numbers and the numbers indicate not meaning but sequence, the order in which the government invented new ways to enumerate the body.

On the screen above her: "USCIS has completed biometrics for applications filed in March 2023." It is January 2026. The sentence is informational. The information is that you will wait. You will wait until your waiting has been processed by a system that is processing other waiting. The wait is not failure. The wait is the point.

In the corner of the room there is a plant. The plant is fake. The leaves are dusty with a specific dust, the dust of fluorescent light and recycled air. Someone chose the plant. Someone put it in the corner. The plant says: this is a place where living things are. The dust says: this is a place where living things are not maintained.

•

The adjudicator's office is down a hallway and through a door that locks behind you. The desk is gray. On the desk is a computer and the computer is open to a system called CLAIMS 4, which stands for Computer-Linked Application Information Management System, fourth version. The name tells you everything. The applications are linked. The information is managed. The humans are not mentioned.

The adjudicator's name is Karen. She has worked here eleven years. On her desk there is a photo of two children at a beach. The children are smiling. The beach is white. The photo is from six years ago. The children are older now. She does not update the photo because updating the photo would be admitting that time passes and in this room time does not pass. In this room there is only the case in front of you and the case after it and the quota of cases that constitutes a good day.

Karen does not think about the cases as people. This is not because Karen is cruel. Karen is not cruel. Karen is a person who goes home to a house where there is a dog named Baxter and a husband named Ron and a recurring disagreement about whether the upstairs bathroom needs regrouting. Karen does not think about the cases as people because thinking about the cases as people would make it impossible to process the cases and processing the cases is the job and the job is what she has.

There is a code for denied. There is a code for approved. There are seventeen codes for the reasons a case might be sent back to the pile, each code indicating a specific failure of documentation, a signature in the wrong place, a date in the wrong format, a check for the wrong amount. The codes make the decision. Karen enters the codes. The entering is not the decision. The entering is the recording of a decision that the system has already made.

In the training, they told her: you are the last line of defense. They meant against fraud. They meant against the people who are trying to get in who should not get in. They did not tell her how to know which people those were. They gave her the codes. The codes know.

•

In the Sonoran desert there are trails. The trails are not marked on any map. They are marked by other things: empty water jugs, blackened from the sun. A child's shoe, size 4, pink with a strap. Bits of clothing caught on cholla. The clothing weathers. The pink shoe weathers. Eventually there is only the trail and even the trail weathers and new trails are made and the making is the policy.

The policy is called Prevention Through Deterrence. It has been the policy since 1994. The policy says: if we make the easy crossings hard, people will stop crossing. The policy has not stopped people from crossing. The policy has moved the crossings into the places where the crossing kills. The desert. The river. The mountains in winter.

Since 1994, somewhere between eight thousand and ten thousand bodies have been recovered from the border region. The number is uncertain because some bodies are not recovered. Some bodies are bones now. Some bones are dispersed. The dispersal is also the policy. You cannot count what you cannot find.

Karen in her office in lower Manhattan does not think about the desert. The desert is not her department. Her department is benefits adjudication. The desert is enforcement. These are different departments. They have different codes.

But here is the thing the codes do not capture: Karen's denials become the desert. The case sent back to the pile becomes the woman who cannot wait any longer. The visa rejected becomes the father who crosses anyway. The system is one system. The departments are a fiction. The fiction is how Karen goes home to Ron and Baxter and the argument about regrouting.

III. The Men

His name is Tomás. Twenty-three years in. Started in Laredo when Laredo was still manageable, before the walls went up everywhere except where people could see them, which pushed everything into the places people couldn't see. Now he works a sector in Arizona, fifty miles of desert that might as well be the moon.

He joined because his father had joined. His father was Border Patrol in the seventies, back when it was different, back when you knew the guys you caught and sometimes you knew their families and sometimes you let them go with a warning because what was the point, they'd be back next week, same guys, same crossing, everyone just doing their job. His father called them mojados without malice. His father gave them water.

Tomás gives them water too. This is not against policy now, though it was for a while, though some of the guys still pour it out when they find the jugs that the aid groups leave. He does not pour it out. He has found too many bodies for that. He has found women with their lips black and their eyes open and he has found children who did not look like children anymore and he has found men who walked until their feet were meat and then walked further. He does not pour out the water.

He does his job. The job is apprehension. The job is processing. The job is the paperwork that takes a person and makes them into a case number and moves the case number through a system until the case number is on a plane or a bus or, increasingly, in a cell waiting to be on a plane or a bus. He does not make the policy. He does not like the policy. He does the policy.

There is a thing that happens in the fourteenth year. He has talked about this with other guys who have been in long enough. Around year fourteen you stop feeling it. Not because you've become hard. Because you've become something else. You've become the job. The job does not feel. The job processes. You can be a person at home and the job at work and the two do not have to meet.

Except sometimes they meet.

•

There was a girl. There is always a girl when the guys tell these stories, and Tomás knows this, knows he's becoming a cliché even as he thinks it. But there was a girl. Eight years old, maybe. Nine. She had been walking for four days. Her mother was gone. Gone could mean a lot of things. Gone could mean dead. Gone could mean separated. Gone could mean the mother paid extra to the coyote to get the girl through and stayed behind because there wasn't enough for both. The girl didn't say which. The girl didn't say anything. She just stood there in the processing center with her eyes looking at something that wasn't in the room.

He did the paperwork. He did the paperwork correctly. The paperwork went into the system and the system did what systems do. The girl was transferred to HHS custody because she was unaccompanied. Unaccompanied is the word. The word means alone but alone would be too much so they use unaccompanied. She was unaccompanied to a facility in Texas. He does not know what happened to her after that.

He could find out. There are ways. He does not find out. This is a choice and he knows it is a choice and he makes the choice every day he does not log into the system and type her name.

He has a daughter. His daughter is twelve. His daughter is in seventh grade and she is learning about the Constitution and she asked him once what he does, really what he does, and he told her he keeps people safe. She asked safe from what. He said from the people who want to come here the wrong way. She asked what the right way was and he said the legal way and she asked why they didn't just come the legal way and he didn't have an answer that would fit in her twelve-year-old understanding of how things should work.

The legal way can take twenty years. The legal way requires money and lawyers and documents and a fixed address and an employer willing to sponsor and a consulate appointment that might be scheduled for a date after you're dead. He didn't say this. He said some people just don't want to follow the rules. She accepted this. Children accept things.

He goes to work. He does the job. The job is apprehension and processing and paperwork and sometimes the job is finding bodies and calling it in and waiting for the medical examiner and doing the paperwork for that too. There is paperwork for the bodies. There is paperwork for everything.

He does not think about the girl. He thinks about the girl all the time. These two statements are both true. This is what the fourteenth year does to you.

•

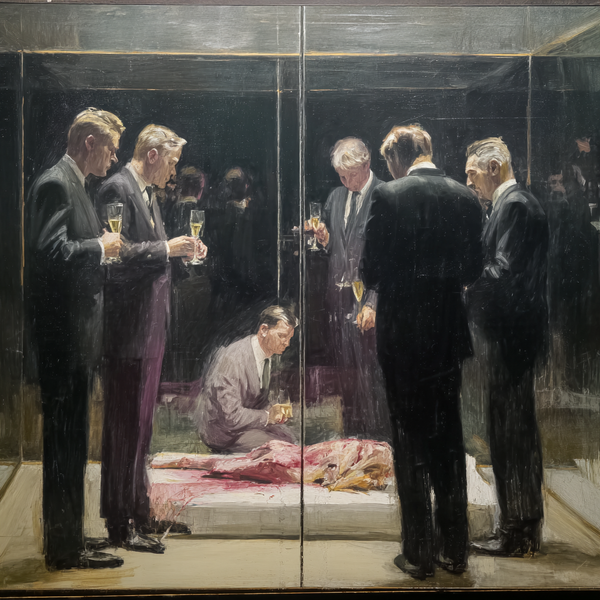

In Washington there is a man who writes policy. His name is not important. There are many men like him. They went to schools where they learned to write policy and now they write policy. The policy uses words like "consequence delivery" and "interior enforcement" and "lawful removal." The words are very clean.

He believes in the policy. This is the thing about him that matters. He is not a cynic. The cynics burn out or move to lobbying. The ones who stay are the ones who believe. He believes that borders are real. He believes that nations have the right to control who enters. He believes that the United States is a nation of laws and the laws must be enforced or they are not laws.

He has never been to the desert. He has never been to a processing center. He has seen photographs. The photographs are in reports and the reports are on his desk and he reads the reports and writes the policy and the policy becomes the desert and the processing center and the photographs in new reports.

There is a circularity here that he does not see because seeing it would make the job impossible. He is not paid to see the circularity. He is paid to write the policy. The policy is good if it achieves its metrics. The metrics are apprehensions and removals and something called "deterrent effect" which cannot be measured but must be invoked because without it none of the other numbers make sense.

The numbers have never made sense. Since 1994, when Prevention Through Deterrence became the policy, unauthorized crossings have continued. The policy that was supposed to deter has not deterred. It has only moved the crossings and increased the deaths and created the industry of smuggling that now controls the routes. He knows this. The reports say this. He writes new policy anyway. The new policy is more of the old policy. More wall. More agents. More consequence delivery.

He tells himself: if we stop now, it will have been for nothing. All the money spent. All the deaths. If we stop now, we admit that the policy was the problem. So we cannot stop. We can only do more.

This is the logic of the quagmire. He learned about quagmires in school. Vietnam. The inability to exit because exiting would mean the sunk costs were sunk. He wrote a paper about it once. He does not recognize that he is living inside the paper he wrote.

IV. The Complication

Here is what the essay so far refuses to say: some of the fear is real.

Not the great replacement fantasy. Not the caravan panic. Not the demographic terror that has no basis in anything except the imagination of people who have never met their neighbors. But some of it. Some of the fear.

There is a town in Texas where a girl was killed by a man who should not have been in the country. The man had been deported twice. He came back. He killed her. This happened. It is a fact. The fact does not justify the policy but the fact exists and the people who use the fact to justify the policy are not entirely making it up.

There are smugglers who are not sympathetic. There are cartels that control the routes and the cartels are brutal and the brutality does not stop at the border. There are people who come for reasons that are not persecution or poverty. There are criminals. There are predators. There are people who would do harm.

The captivity narrative is a lie that contains a truth. This is how the lie works. This is why it works. If it were entirely false it would not survive. It survives because somewhere inside it there is a body. The girl in Texas. The woman who was assaulted. The family whose house was broken into. The bodies are real. The lie is in the multiplication. The lie is in the taking of one body and making it into a million bodies. The lie is in the arithmetic.

The people who fear are not all racists. Some of them are. Many of them are. But some of them are people who had something happen. Or people who know someone who had something happen. Or people who are afraid of having something happen because they live in a country that gives them nothing else to hold onto. No healthcare that works. No job that lasts. No neighborhood that stays the same long enough to feel like home. The fear finds an object. The object is the one who just arrived.

This does not make the fear correct. This does not make the policy just. This makes the fear human. And the essay that does not admit this is an essay that is lying to itself about its own righteousness.

•

There is also this: some of the taken become takers.

The Border Patrol is forty percent Hispanic. Tomás is not an exception. He is a demographic. The men who do the apprehending are often the sons and grandsons of the apprehended. The second generation builds the wall against the first.

This is not hypocrisy. Or it is not only hypocrisy. It is something more complicated. It is the logic of arrival. I am here now. I came the right way. Or my father came the right way. Or my grandfather came some way that we now call the right way because it was long enough ago that the way has been forgotten and only the arrival remains. I am here. They are there. The line must be held.

The Irish built the signs that said No Irish. The Italians voted for the laws that kept out Italians. The Jews closed the door behind them. Every wave becomes the shore that the next wave breaks against.

The captivity narrative is not only white. The captivity narrative is American. And American is a thing you become by agreeing to its terms. The terms include the forgetting of how you came. The terms include the fear of those who come after. The terms include the wall.

V. The Return

She is walking north. Her name is something I do not have the right to invent. She is not a symbol. She is not a device. She is a person I cannot write because I do not know her and the not-knowing is the point.

This entire essay is a captivity narrative. An American explaining America to Americans using the tools Americans made. McCarthy and DeLillo and Greene. Rowlandson and Parker and McCain. The tools are American. The frame is American. The fear of the frame is American too.

She is outside the frame. She is walking north for reasons the frame cannot hold. The reasons are hers. The form in the processing center has a box for the reasons and the box is too small and the smallness is the policy and the policy is the frame and the frame is this essay and this essay is the captivity.

I cannot free myself from the narrative by writing about the narrative. The writing is inside the narrative. The critique is inside the critique. The recognition that America cannot recognize itself is still American and still a failure to recognize.

She is walking north. She will arrive or she will not arrive. She will be apprehended or she will not be apprehended. She will be processed or she will be bones in the desert and the bones will be processed too, eventually, by the sun and the animals and the forgetting.

•

The captivity narrative requires a return. Rowlandson came back and wrote the book. The POWs came back and ran for office. The return is the telling. The telling is the point.

But what would it mean to not return. To stay in the wilderness. To become the thing the narrative cannot hold.

Frances Slocum did this. Cynthia Ann Parker tried to do this. They refused the return. They said: I am not who you say I am. I am not captive. I am home.

The nation could not accept this. The nation sent Rangers to bring Parker back. The nation let Slocum die in what they called exile. The nation requires the return because without the return there is no story and without the story there is no nation.

She is walking north. She does not know that she is walking into a story. She thinks she is walking into a country. She thinks the country is a place. The country is not a place. The country is the story it tells about the place. The place is the desert and the river and the wall. The story is the captivity.

I do not know how to end this. The ending would be a return. The return would be a lie. The lie would be American.

So instead: she is walking north. The sun is coming up. The light is the color of nothing, the color of heat before the heat becomes killing. She has water. She has her reasons. She does not have the story.

The story has her.

© 2026 August Holloway / Dead Letter Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form without prior written permission.